Introduction

There are many factors that contribute to the degree of success that a new company can achieve. Some have argued that timing is the biggest factor determining the degree of success of a new company, and I largely agree with that position.

Another factor how you build your business around the costs of the product. That is the focus of this post.

I look at:

Costs to create the initial product - going from 0 to 1 [see footnote]

Marginal cost of each unit once you’ve gone from 0 to 1

Marginal cost of each variant of the product, so you can sell new products to existing customers

Amortizing the costs it took to go from 0 to 1

Cost of branding and customer acquisition

To summarize this post, the ideal new company focuses on creating a product that doesn’t exist, will have low-to-zero marginal costs, will have low-to-zero costs to create variants so you can have early recurring revenue from customers, the market will be large so that development costs can be spread across many customers, and you enter a market that is small without an existing 800 pound gorilla so you can establish a brand.

Note: those last two points are contradictory (big market to amortize costs and small market to build brand)

The solution to the contradiction is that the company is creating a product for a category that is currently small or non-existent but will soon explode in size. On other words, timing.

Costs to create the initial product

The cost to create the initial product is the cost to go from 0 to 1. It is the cost to get the very first unit of the product that can be used by a customer.

On one hand, you, as the owner of a new company, want this initial cost to be as low as possible. You don’t want to acquire a lot of debt and financial risk (or sell a large amount of your business) before you start generating revenue.

On the other hand, if it is quick and easy to go from 0 to 1, other companies can duplicate your product, creating a lot of equivalent competition, and making it very hard to impossible for you to make a profit.

Ideally, you have acquired a special set of skills or knowledge that make the costs of getting from 0 to 1 not too high for you but very high for anyone without your set of skills or knowledge. You want to leverage the scarcity of your skills or knowledge.

Marginal cost of each unit

Once you’ve create the first unit of your product (you have gone from 0 to 1), what is the cost to create each additional unit?

The original example I read about was the cost of creating cans of soup. The cost of the first unit, “Can 1”, is extremely high because you first need to build a factory to create the cans of soup. Each subsequent can of soup (Can 2, Can 3, …), however, can be produced very cheaply. (See Figure 1)

Software takes this to an extreme. There is still a potentially large up-front cost before the 1st unit of software can be sold to a customer (you have to create it), but the cost of each subsequent unit of software, especially in the age of electronic distribution, is effectively $0.

High-tech hardware with lots of expensive components is the opposite. The cost to go from 0 to 1 for hardware is very high, and each additional unit that can be sold to a customer still costs a lot. If you are producing high-tech hardware, you do not benefit from low or zero marginal costs.

For your company, the marginal costs of software is much more attractive than the marginal costs of hardware.

Figure 1: Marginal cost for each duplicative unit

Marginal cost of each variant of the product

Once you have created your first product and sold it for a while, eventually new customers who have not bought your product become hard to come by. Sales slow down.

To address this, you need to produce your second product and start the process again, often selling the new product to the same customers who bought the first product. That is, you increase the customer lifetime value.

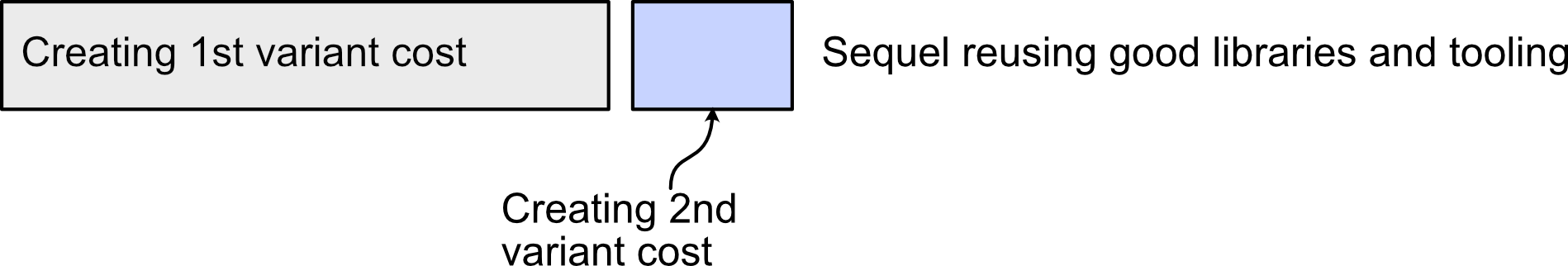

You could produce an entirely new product from scratch, but this is just as expensive, and sometimes more expensive, as creating the first product (see Figure 2). Cyan took this approach. It took Cyan 2 years to develop Myst, but it took Cyan nearly 4 years to develop the next variant, Riven.

Figure 2: Creating the next product from scratch

An alternative, especially with software, is to focus on creating reusable libraries and tooling while developing the first product. This can push out the time and increase the costs to go from 0 to 1 for the first product, but leveraging these libraries and tooling can dramatically reduce the time and costs going from 0 to 1 for the second product (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Creating variants by reusing libraries and tooling

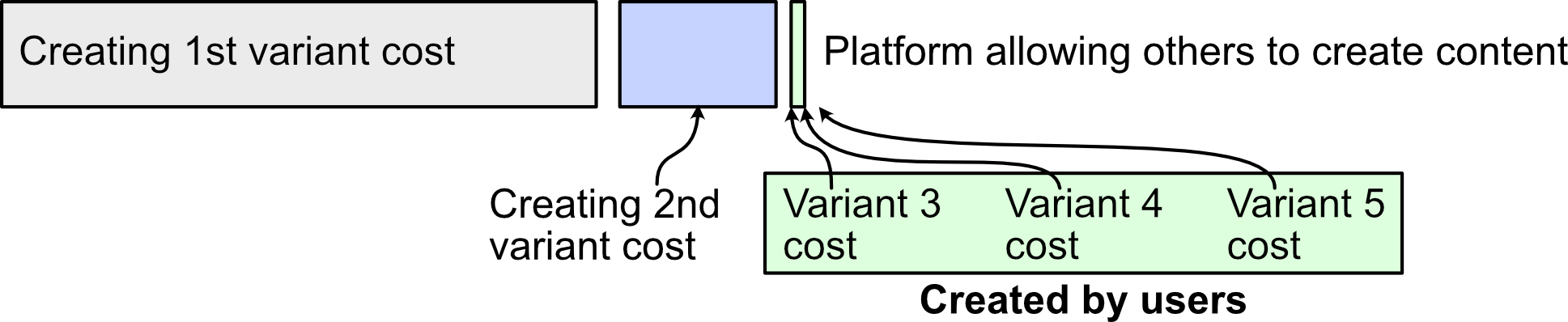

Pushing the libraries and tooling re-use even further, you can make the libraries and tooling available to others to create variants for you at no costs to you (see Figure 4).

With software, the marginal costs of each duplicate unit of the already created product is $0. With platforms, the marginal costs of each new variant is also $0. The costs for the variants are borne by 3rd party creators. You just need to make sure you can capture a reasonable amount of the revenue.

Roblox pursued this strategy, went public on March 10, 2021, and as of this writing (March 27) the company is valued at $39 billion.

Figure 4: Creating variants by being a platform

Amortization and economies of scale

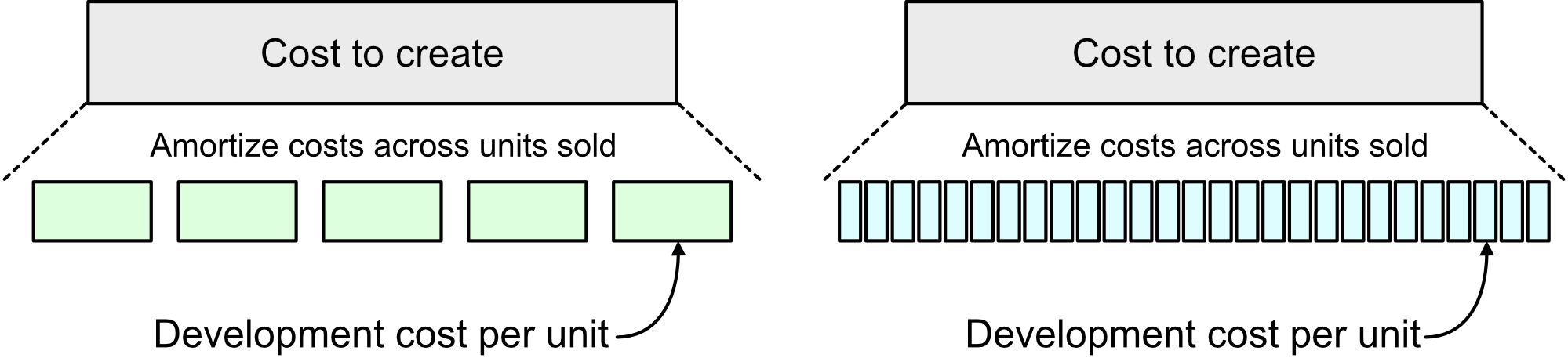

As discussed in “Marginal cost of each unit”, creating the first unit is very expensive, often in the millions of dollars. However, you typically don’t sell that first unit for $50 million and then each subsequent unit for $2.

Instead, you estimate how many units you will be able to sell and then spread (or amortize) the $50 million development costs across all those units.

Figure 5: Amortizing development costs across a small or large number of units

Figure 5 shows that if you expect to sell a small number of units (the diagram on the left), the development costs borne by each unit sold will be relatively high, so the price to the customer must be relatively high.

If, on the other hand, you expect to sell a large number of units (the diagram on the right), the development costs borne by each unit sold will be relatively lower, so the price to the customer can lower.

Thus, ideally the size of the addressable market should be quite large, and the percentage of that market you can capture should also be quite large.

If these two combine, you can enter a virtuous cycle (see Figure 6). An expected large market that can be captured leads to a lower amount of the development cost that must be borne by each unit sold. A lower cost per unit creates the opportunity to lower the price to customers. Lower prices to customers increases the number of units sold. With an increase in the number of units sold, the lower the development cost borne by each unit.

Figure 6: Virtuous cycle

When marginal costs are low (or zero), volume is an incredibly important aspect of pricing.

Furthermore, as you achieve volume and can lower prices, you create a barrier to entry to new competitors because they won’t be able to match your low prices.

Branding and customer acquisition costs

The discussion so far has been about the cost of the product - how long it takes to initially create a product, the cost of each additional unit of that product, the cost of each new variant of the product, and the development cost that must be borne by each unit sold.

However, the cost of acquiring each customer must also be considered.

In our minds when we form a company, the value of our product will be self-evident, every possible customer will know about the product, and every possible customer will trust you enough that they will pay for the product.

We can all dream. 🙂

In practice, customer costs can be very expensive.

Selling into an enterprise, while seemingly attractive because of the potential size of a sale, is particularly challenging. Finding the right person in a company to contact, establishing a meeting to make your pitch, waiting for all the stakeholders in the enterprise to weigh in, getting the green light for a proof of concept deployment, carrying out the proof of concept deployment, and then getting the company to agree to cut a check can take months.

If you are going after the enterprise market, you need a lot of money to survive these very long sales cycles.

Here, branding helps.

Back in the 1980s I often heard the line

Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.

In the early 2000s that line could probably have been applied to Microsoft.

A solid brand opens a lot of doors and greases a lot of skids.

But… as a new company you don’t have a brand that can help open the doors.

Even if you are selling to individual consumers instead of into the enterprise, a brand can be incredibly valuable.

In the consumer space we buy books by authors we know and trust. We see movies staring actors we love or directed by someone whose films we’ve enjoyed before. We go to a familiar chain restaurant in an unknown city because we know what to expect from that brand of restaurant.

Establishing a brand in the minds of potential customers is a complex thing on which thousands of of books have been written.

My attempt to summarize the knowledge in those thousands of books into a single statement is: You want your product entering a market or segment of a market that is initially small without an existing 800 pound gorilla.

This, of course, contradicts the previous sections of wanting a large market in order to amortize development costs across a large number of units that will be sold.

The solution to this contradiction is to enter a small market that is about to explode in size.

This comes full circle to timing being the biggest factor in a new business’s success.

Conclusions

Using product costs as a lens through which to evaluate the viability of a new business - whether you are creating the business or investing in it - can be valuable. It helps inform the questions that must be answered when evaluating the potential of the business.

* “Zero to One” is the title of a book by Peter Thiel. Thiel’s book is about creating the dominant business in a new product category. In this blog post, I am talking about a new company creating the first sellable instance of their product. Too many companies die before they even get to this point, and then too many companies fail to consider the costs of instance 2, 3, 4, and so on, then the next product variant, and establishing recurring revenue from a customer. Many of these others costs (or failure to account for them) have their roots in the decision process it takes to reach the first product you make.